The university showcases deep relationship between the movement and its school of design

By Joseph Boisvere

In graduate school I took a course on Latin American cinema that primed me for this show, The Bauhaus and Harvard, which is organized in conjunction with the centennial of the founding of the Bauhaus in Weimar, Germany. But Bauhaus is a German movement, and Germany is not in Latin America, you might reasonably argue. Fair. However, during this course on films of the western hemisphere I was fortunate to be exposed to Arturo Escobar’s brilliant book from 2018 Designs for the Pluriverse: Radical Interdependence, Autonomy, and the Making of Worlds. In it, Escobar makes a sophisticated argument over many chapters that I can sum up briefly: Design is everywhere in human society, and how a culture, a person, a movement, designs anything – from tools to buildings to works of art – is indicative of a unique perspective on how the world works, how it is created and dwelt within, and the designer’s role within this world.

This is a brilliant reversal of the practical logic of Bauhaus, in a certain sense, which took aesthetic intentions and married these to the pragmatic concerns of design. Harvard’s retrospective on the relationship that the university enjoyed with Bauhaus and its contributors is a succinct and yet varied look into not only some interesting outcomes of this design but also the training that students of design at the university’s campus during the dominance of Bauhaus underwent.

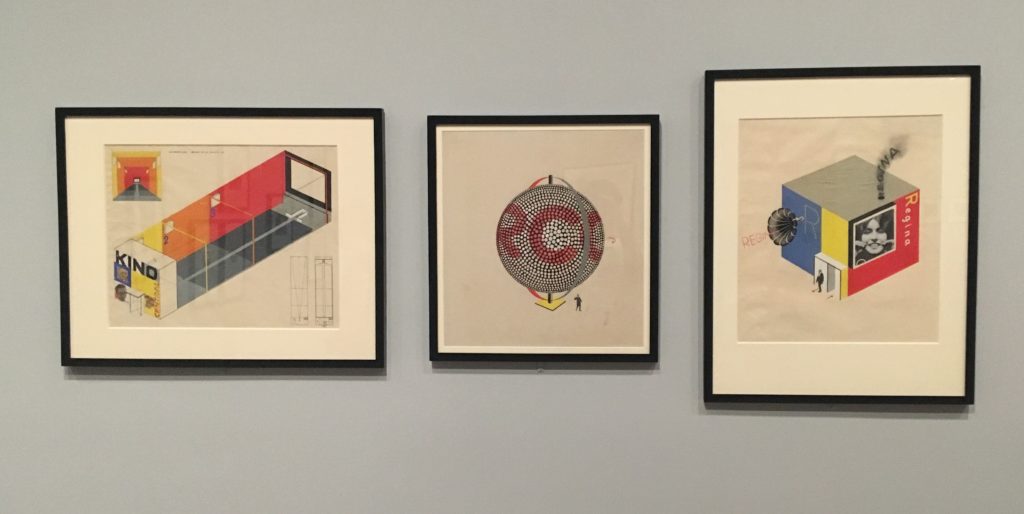

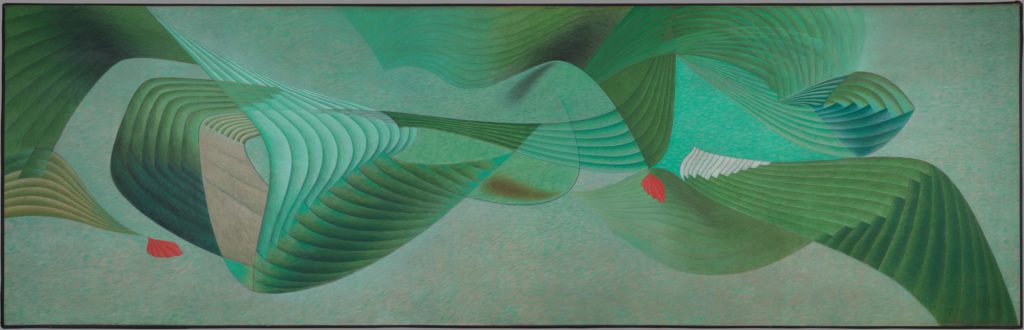

Studies and exercises in color, line, and form appear not only beside furniture and architectural diagrams, but alongside drawings by Kandinsky, a massive wall-mounted sculpture by Hans Arp, and a twenty-foot long painting by Herbert Bayer which once hung in Harkness Commons. Semi-industrial samples of Bauhaus weaving hang like tapestries as testaments to the rigorous workshop training that designers were expected to complete. The show is laid out in a way such that these very different artifacts occupy a space that tells a story, not as you walk through as in some retrospective shows, but in its very amalgamation. The various media lain one next to another suggest that the show’s layout itself is utilitarian, demonstrative, and aesthetic all at once.

A century after Bauhaus rose out of the ashes of the first World War, this retrospective on its integration into Harvard’s School of Design closes the gap even further between the purely aesthetic and the necessarily pragmatic. It gives its audience a hint as to what Escobar argued in his recent book: that design is ubiquitous, even a retrospective art and design show performs a function as it entertains. Bauhaus at Harvard reminds us to appreciate the aesthetical qualities of the utilitarian and to expect beauty from that which may otherwise be merely useful.